How Can We Create an Architecture That’s Built to Last Because It’s Designed for Change?

This is the continuation of part of an ongoing series, where I’m using the framework of WHY, WHAT, HOW, WHO from my book Blind Spot: A Leader’s Guide To IT-Enabled Business Transformation – enhanced with stories and analogies – to help business leaders to understand the Digital and IT transformation journey in very simple business terms.

The crisis of the last few months should have clarified WHY we need to change, and that the time is NOW (Part 1). Only a few senior leaders are still wondering about or resisting that premise. One real challenge, for the entire executive team, is to think about WHAT will make us faster and more flexible, which is “Business Agility” (Part 2). Of equal importance, this time, HOW we architect and build modern systems matters – a lot – because we can’t have Business Agility if we keep adding to our Technical Rigidity.

Part 4: HOW We Build IT to Last by Designing for Change

In my most recent blog post, I got started with the critical concepts of the HOW we built so much complexity, cost, and rigidity into our IT landscape. I also leaned into the future with the concept of a puzzle “box top” of what the technical landscape should look like in order to simultaneously achieve the Business Outcomes (value) and the Technical Outcomes (agility). That intersection will set up the Organization Outcomes (productivity) required to continuously transform well into the future.

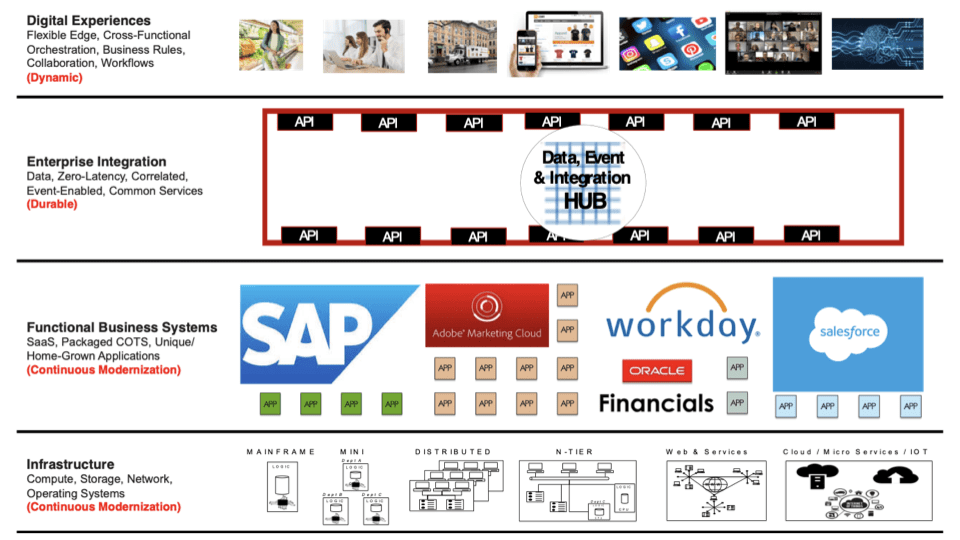

In this post, I’ll describe my learning journey over the decades and across several eras of technology. There are durable patterns, regardless of era, and, fortunately, the technology revolution is playing into our favor, and, now, the possibilities are practically limitless. Going forward, it’s just a matter of getting the right architecture and having the discipline, patience, people, and planning to execute and set the foundation for future flexibility. HOW we build WHAT we build will be the key differentiator as we compete in the future.

Durable Concepts Enabled by Modern Technology

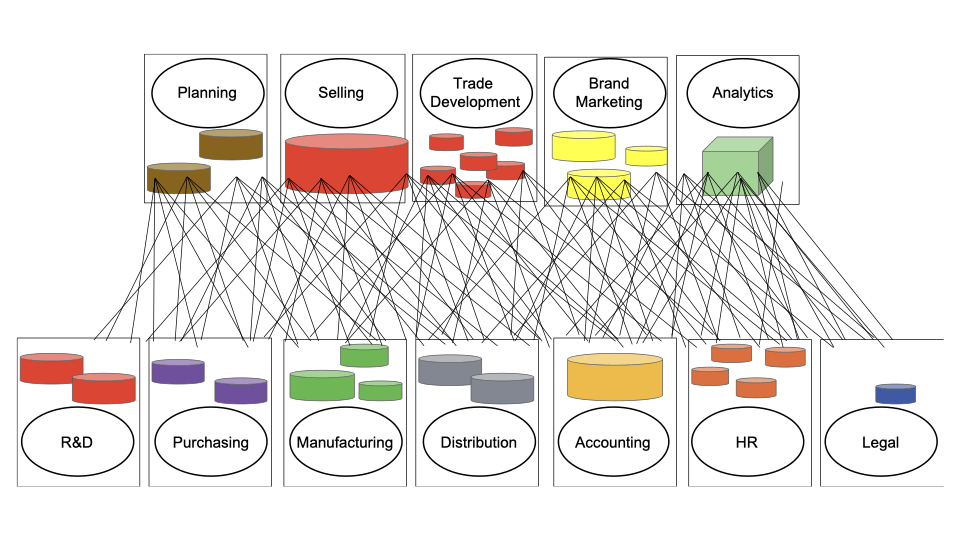

Over the decades, we thought of systems mostly for functional efficiency and executing very straightforward processes at scale – as we grew our companies. So, our picture, if we had one, typically told us to build systems as self-contained functional monoliths, with all layers packed together vertically. For example, an order entry system had the application, business rules, user interface, data, messaging, and infrastructure all tightly coupled together. We repeated the pattern for other systems too. Each system had its own hardware, programming language, business logic, and data. Most of the time, each application had its own and different definition of key data elements like customer, product, location, prices, etc. So, it was difficult to then connect order entry to supply chain to customers to invoicing, and other similar integrations, unless we hardwired those separate systems together and added more complex code and logic and created more redundant databases. This, all together, made it very hard to change business rules or processes, to harmonize data across systems, and to maintain the connectivity of the systems when anything changed in one of the individual systems. Here’s an example of the picture created in the early days of my IBM career when Frito-Lay was my main client account.

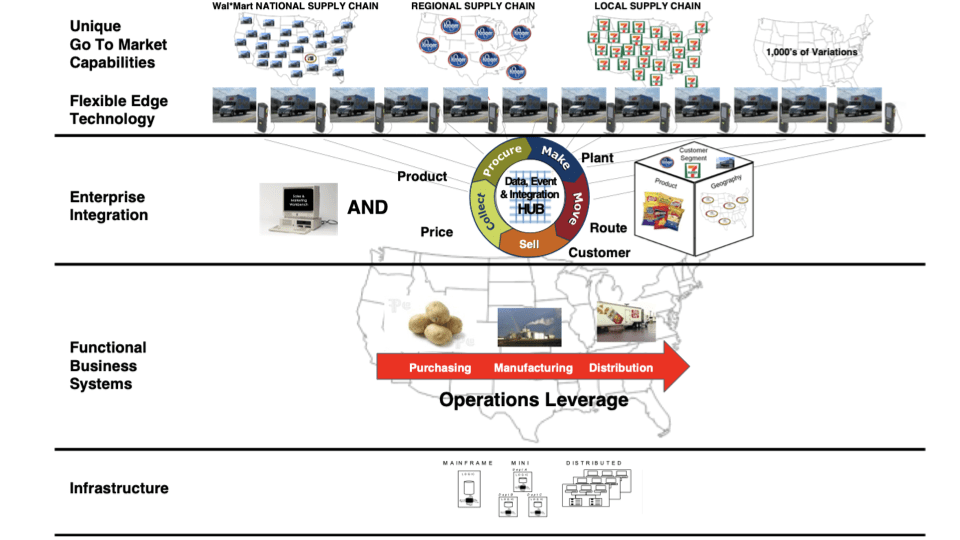

As I moved into the CIO role at Frito-Lay in the early 1980s, the big shift in architectural design was forced on me and my team. It began when we had to deal with the “Wal*Mart Effect” (not unlike the modern “Amazon Effect”). Wal*Mart was at the leading edge of retailers asserting power on consumer goods companies. Unlike most traditional retailers who wanted to run periodic promotions at a regional or local level, Wal*Mart wanted “Everyday Low Prices” everywhere. Soon after, many other retailers followed Wal*Mart’s example, but not all of them did. This drove the requirement at Frito-Lay for us to have the capability to provide different pricing, promotions, and products for each retailer. But also, we had to preserve our scale advantages through supply chain, manufacturing, human resources, branding, and financial capital leverage. We had to think of horizontal layers and platforms that could be consumed by various applications. We had to draw a different “box top” to guide us in putting together this new puzzle. This was the picture we drew of Frito-Lay’s future Business and Technical Agility.

The picture was great, and the concept has been durable over time. However, our implementation was crude back then because there were severe technology constraints at that time. But, despite those constraints, it worked and was productive. We achieved three necessary forms of agility.

Renewal Agility: By building more horizontal platforms in layers, we were able to continuously and incrementally evolve our hardware, networks, databases, and software at the appropriate paces for their own unique innovation cycles. For example, PCs were replaced every 2-3 years, handhelds every 5-7 years, but our mainframes in the data centers could last 7-10 years without replacement. All of this change could now happen with a steady, low-level ongoing investment and little to no disruption for the business.

Strategic Agility: Because we had built enterprise data, separated out business rules, and created common services in the new architecture, adding new capabilities, even cross-functional capabilities like new product development and introductions, came in weeks or months rather than years. This was possible because we assembled things by consuming/reusing existing components rather than building things from scratch. IT was no longer the bottleneck or the long task in any strategic initiative.

Tactical Agility: We had the flexibility to price and promote at the customer and store level and to know every bag in every store and profitability at the route level. We couldn’t do it “in the moment” or real-time with the technology of the time, but we did get updates daily and could adjust weekly. This was a big step forward from our old pattern of doing national pricing and changing only two times per year.

The same design approach was key to my experience as the CIO of BNSF Railway in the mid-1990s. The key business strategy – for customer service and cost efficiency and operating ratio business outcomes – was the idea of running a “scheduled railroad”. To make that happen, we had to use technology to more accurately reflect and align the “electronic railroad” (the data about the railroad) with the “physical railroad” (the trains and cars and crews themselves). At the time, the technology had progressed but was still not truly real-time. We used toll tags and fixed proximity readers. The technology solution wasn’t ideal, but it did bring knowledge (front-line, detailed, in the moment facts) and perspective (ability to see the big picture, recognize patterns, and make decisions) closer together. Improved Technical Agility led to improved Business Agility.

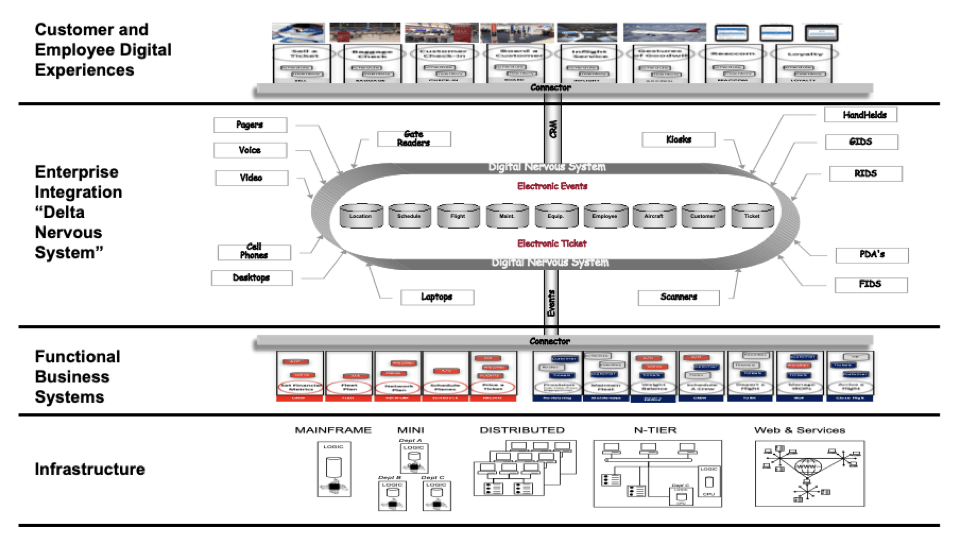

This experience at BNSF was followed by our work on the Delta Air Lines “Digital Nervous System” which connected planes, crews, passengers, gates, baggage, customers, etc.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, we used event publish-and-subscribe technology and business rules and correlation engines to gather, correlate disparate functional data from the front-line of the airline. The technology innovation was marching forward. The concepts were the same as back in the Frito-Lay days, but the implementation was getting better as the available technology matured. This integrated picture of the “state of the airline” was updated in real-time and provided, as needed, to every part of the organization. For example, we could know (SENSE) that the flight was going to be late due to a mechanical problem and a snowstorm in the Midwest (CONTEXT). And, by correlating this knowledge and context to Crew business rules, it became clear that the crew flying that plane would “time out” (EVENT), hours before it actually happened. As a result, we could have a fresh crew in place and ready to go (RESPOND). That ability to have a persistent, accurate, and full electronic picture of the airline was what enabled Delta’s dramatic rise from the bottom to the top of industry rankings for customer service, on time performance, and operational efficiency. Those business outcomes were made possible by, as you might be able to guess by now, Tactical and Strategic Agility that was enabled by the new technology architecture.

Come forward to today when Uber, as an example, can use GPS, smartphones, in-memory/in-motion events, external data sources for situational awareness, and AI/ML to sense-and-respond in the moment and serve customers and drivers through a modern digital experience. Also, as Uber has a new idea, like dynamic pricing based on weather or traffic, they can quickly make a strategic pivot to add those capabilities (either homegrown or third-party) because they’ve architected and built reusable components that are easy to connect, assemble, and configure. Uber, and several progressive companies we work with today (e.g. FedEx), use modern technologies to implement these durable architectural patterns. They use modern puzzle pieces to build out that “box top” picture in a better, faster, and more flexible way.

From the Frito-Lay story of the 1980s to the BNSF and Delta stories from the 1990s-2000s to the FedEx and Uber stories of more recent times, there’s a pattern. All of these stories across all of these eras have these big ideas in common.

- Each layer or platform could be changed at different speeds and times. For example, the infrastructure could be migrated as networks (think 5G in the modern era), servers, and storage technology (think next generation of Cloud in modern era) changed. Due to rapid evolution by the technology hardware providers, that infrastructure platform will need to change more often than the much more stable data platform.

- Building with the big picture in mind allowed us to create common, reusable components, services, and data so that we could quickly assemble and configure new functional and cross-functional business capabilities as new opportunities and threats emerged and business strategies changed.

- We could change the orchestration layer, where the business rules are, much more flexibly and frequently. Designing and building things horizontally in layers allowed us to abstract the business rules out of the application. So, rules, such as pricing or promotions being offered, could be unique by customer, product, and geography and could be easily and flexibly changed – seasonally, by day, or even “in the moment” – by business decision makers or by artificial intelligence/machine learning rather than by IT programmers.

In today’s world, there are few constraints. If we have a business vision, technology can make it happen. If we want agility and need to be able to change and pivot quickly, the technology is there to support that kind of continuous transformation. If we have the right puzzle box top and economic model that supports a wider aperture to invest in foundations and platforms, we can accomplish anything we can envision. This is no longer breakthrough thinking for tech-savvy IT leaders. They would know this and be running this play if they were able to start with a clean slate, without decades of legacy systems rigidity. The difficulty is modernizing and transforming starting from a rich but complex legacy base. Dealing with this complex, multi-year, transformation campaign requires a Current State and Future Vision picture (“box top”) and some high-level, phased snapshots (“time-elapsed photography”). Once you have that…

It’s All About Execution: The Financial HOW and the WHO

If we take all of the technical jargon out of the conversation, these concepts are rational and fairly easy to understand. Yes, we can accomplish anything we can envision. However, the difficulty is in the execution – the people, the investment, and the operating model.

The complexity of the legacy base and HOW we’ve built things over time, given the Vicious Cycle, is getting to a critical level of rigidity, cost, and risk. And, over the last decade or so, there has been a steady retirement of the talent (the WHO) that built these systems in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. So, our ability to effectively and efficiently run, much less to renovate and replace, these systems is rapidly dwindling every year. The thought of continuing to put this off and “get to it later” is unimaginable. Now is the time to deal with it.

If we want modern business and architectural outcomes (WHY, WHAT, and HOW), we’ve got to enable execution with new ways of doing things.

- Economic Model (the rest of the HOW)… wide-aperture, multi-year planning of technology as a “Digital Fabric” to invest in continuously, rather than an overhead, cost-center department to squeeze during annual budgeting.

- Organization Model (the WHO)… structure, leadership, workforce, and a culture of continuous transformation that has business and IT working as one unified team

These are the domains of the CFO and the CHRO, in partnership with the CIO. The next few blog posts will frame and inform the new operating model required to change the game and enable winning and THRIVING in an exciting future.

Author: Charlie Feld, Founder and CEO, The Feld Group Institute

Further Learning

If you are interested in learning more about this topic, additional resources can be found on our site, including Leading The Acceleration Of Digital Transformation Part 1: WHY the Time Is Now, Leading The Acceleration Of Digital Transformation Part 2: The WHAT Is Business Agility, and Leading the Acceleration of Digital Transformation – Part 3: Changing HOW the Technology Is Built.